Fortune News | May 25,2024

Sep 1 , 2024

By Tsedeke Y. Woldu

The decision to float the Birr is a game-changer, sparking a mix of anxiety and excitement as it holds the promise of stabilisation. Apprehension is in the air in the streets of Addis Abeba. But here's the silver lining: as inflation is expected to decrease, the bold policy choice could eventually restore balance, argues Tsedeke Yihunie (tsedeke.woldu@gmail.com), a founding CEO of Flintstone Engineering S.C.

The policy decision to float the Birr in July 2024 was both anticipated and shocking. For months, rumours of a steep devaluation had circulated, yet when the moment arrived, it sent ripples of fear and uncertainty through the country and its diaspora.

In Addis Abeba, the reaction was unmistakable. People were worried about the value of their hard-earned income. However, the anxiety was not limited to those trading in foreign currencies; even those with no direct exposure to the Dollar felt the impact, convinced that harder times were on the horizon. The sentiment on the streets was summed up by a common saying: “The trouble with folks is not that they don’t know, just that what they know ain’t so.” Nonetheless, there are good reasons why the average household need not be overly concerned about Birr’s new float.

The policy decision was expected to reduce inflation. The federal government is committed to limiting domestic borrowing, increasing revenues, and pushing state-owned enterprises to become more efficient. These measures should keep inflation sourced in the monetary front at bay, the kind driven by an unchecked increase in the money supply. With less money flooding the market, the value of the Birr is expected to stabilise over time, addressing one of the primary fears associated with the currency’s float.

The cost of imported goods may not spike as dramatically as feared. Historically, import prices in Ethiopia have been inflated by exporters’ need to compensate for the losses they incurred when surrendering a portion of their foreign currency earnings to the National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) at below-market rates. To recoup these losses, exporters often resorted to importing consumer goods and selling them at inflated prices or auctioning their foreign currency earnings to other importers at a high premium. This practice, driven by the scarcity of foreign exchange, contributed to a parallel market where exchange rates were artificially high.

With surrender requirements removed and a more transparent exchange rate in place, the cost of imported goods should become more reflective of actual market conditions. The past month has already shown a moderation in exchange rates, with the market finding a balance at rates below the previously inflated parallel market levels.

Finally, the local (Birr) prices of essential export commodities like sesame, coffee, gold, incense, and flowers are expected to rise. These commodities, which were previously constrained by restrictive export policies, now have the potential to generate higher revenue.

As a result, wages for labourers in the tradable commodities sector and the broader non-tradable service sector are likely to increase. While the Penn Effect suggests that wage increases often accompany inflation, offsetting any real income gains, this may not hold true in Ethiopia, where unemployment hovers near 30pc. In such a labour market, wage increases could genuinely improve living standards without being eroded by inflation.

There are, of course, lingering concerns. One immediate issue is the potential doubling of base prices for taxation purposes. However, this does not necessarily mean that government revenue from tariffs will double. The final price consumers pay is a function of multiple factors, including the tax component, the intrinsic value of the goods or services, and sellers' profit margins. Household incomes set a ceiling on how much prices can rise; sellers, tax authorities, and consumers will all need to adjust to maintain a sustainable balance.

For businesses, the recent economic reforms — such as the government’s restraint from unlimited borrowing, the central bank’s enhanced autonomy, and the liberalisation of interest and exchange rates — are generally seen as pro-business. But the abrupt nature of these changes, including a surprise float of the Birr and the evacuations of eminent domain along Addis Abeba’s main streets, has left the business environment in a state of shock. As brokers in the city describe it, “the market is petrified.”

The scramble among banks to secure foreign currency assets has led to a near-freeze in other sectors, with buyers and sellers of assets largely retreating from the market. Federal and regional authorities' attempts to control prices, particularly for essential goods like edible oil, may have exacerbated this paralysis. The deeper issue lies in the complex interplay between finance and real estate.

Ethiopia’s real estate market has long been influenced by external factors, particularly the availability of foreign exchange. Robust coffee prices, a strong flow of remittances, and the opening of Franco Valuta have all historically driven up property sales and, consequently, input costs. However, the financialisation of housing is not unique to Ethiopia.

Globally, real estate exerts a considerable influence on financial markets. In 2022, the global outstanding securitised debt reached 130 trillion dollars, while the total value of global real estate stood at 380 trillion dollars, more than 30 times the value of all the gold ever mined. Despite its small size, Addis Abeba’s real estate market plays a critical role in the domestic economy, with property values closely tied to the pressures on the foreign exchange market.

The international community’s support for Ethiopia during this demanding time is as much about geopolitical strategy as it is about economic aid. The International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Bank, and other multilateral financial institutions are keen to see Ethiopia overcome its financial obstacles. Their backing of the Birr in the face of market pressures is part of a broader deal to help Ethiopia realise its economic potential. The success of these reforms, however, depends on the relationship between the state and the business community. Constructive engagement between these two entities is crucial if the country is to move forward.

Historically, state-business relations in Africa have been characterised by patrimonialism rather than development-oriented partnerships. Ethiopia cannot be an exception. Although there have been efforts to institutionalise public-private dialogues (PPDs), these discussions have rarely addressed critical issues like the liberalisation of the foreign exchange market. For Ethiopia’s reforms to succeed, the crucial players in the forex market need to be clearly identified and included in these dialogues.

On the supply side, these players include external development partners, exporters of goods and services, foreign investors, the remitting diaspora, and expatriates with savings in foreign currencies. On the demand side are seasonal exporters and importers, perennial importers of essential goods like sugar, wheat, edible oil, medicine, fuel, and fertiliser, as well as the construction and real estate sectors. The financial sector intermediates these transactions, potentially consisting of new foreign banks entering the market, domestic private commercial banks, and the state's policy banks, the Commercial Bank of Ethiopia (CBE) and the Development Bank of Ethiopia (DBE).

The National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) may also play a role if it establishes an investment wing focused on preserving and growing the country’s foreign reserves.

These entities represent a considerable share of national forex transactions, and their participation in a state-business dialogue on forex market governance could help address multiple concerns while unlocking the market’s full potential. One pressing issue is the lack of transparency about the size of the parallel market.

Despite recent moves to reunify exchange rates, little is known about the volume of transactions in this shadow market. Even the official market has become opaque, with few details available on its size. The central bank's recent auction of tens of millions of dollars, a mere fraction of the market’s demand, was tightly controlled, with limits set on bidders, contrary to the terms of the IMF’s Extended Credit Facility. This auction, the only one so far, apparently requires more open and frequent market operations to build market intelligence.

Another critical issue for the state-business dialogue is the planned removal of capital controls. These controls, including hedging limitations and foreign direct investment restrictions, impede the country’s liberalisation efforts. A clear, jointly developed path toward full capital account liberalisation is essential. The hierarchy of the exchange market, from individual remittance accounts and the Office of Exchanges to banks and the central bank, also needs to be clarified and managed with intelligent pricing tools.

The scope of necessary discussions is vast, ranging from developing a capital market and stock exchange to measures for mitigating capital flight and reserve depletion. Coordination among the various stakeholders is crucial to achieving the overarching goal: making the Birr a reliable and convertible sovereign currency. While the interests in the forex market are diverse and often conflicting, there is a shared interest in creating a stable and prosperous economic environment.

The federal government should lead this effort by accumulating ample reserves, lowering inflation, and ensuring the Birr becomes a coveted currency in regional and global markets. The floating of the Birr is a momentous step in the right direction, but the journey ahead requires business and the state to work together.

PUBLISHED ON

Sep 01,2024 [ VOL

25 , NO

1270]

Fortune News | May 25,2024

Viewpoints | May 27,2023

Radar | Apr 29,2023

Agenda | Oct 17,2020

Fortune News | Oct 24,2020

View From Arada | Oct 07,2023

Fortune News | Feb 03,2024

Agenda | Aug 04,2024

Fortune News | Jul 21,2024

Fortune News | Jan 19,2024

My Opinion | 110636 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 106978 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 105697 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 103740 Views | Aug 07,2021

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transportin...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By MUNIR SHEMSU

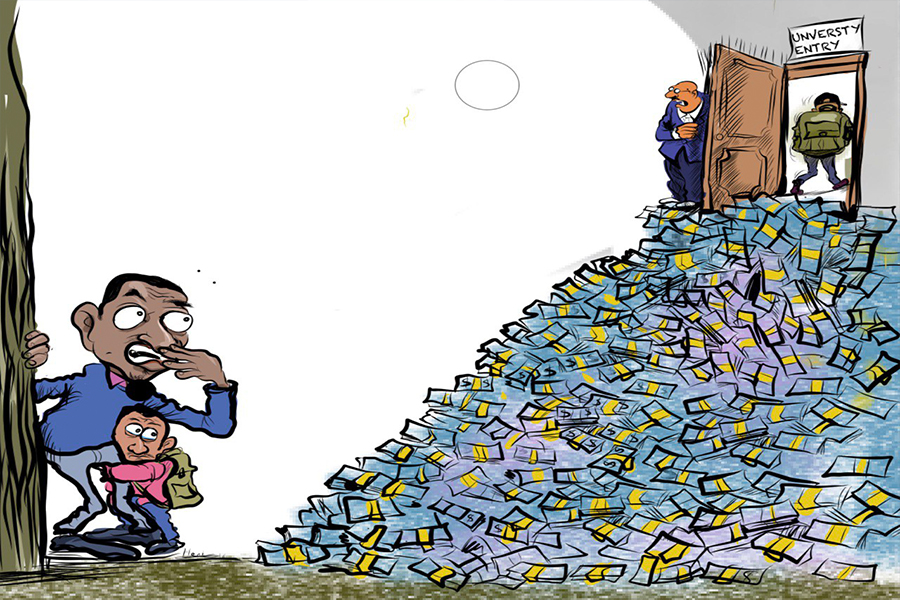

The cracks in Ethiopia's higher education system were laid bare during a synthesis re...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

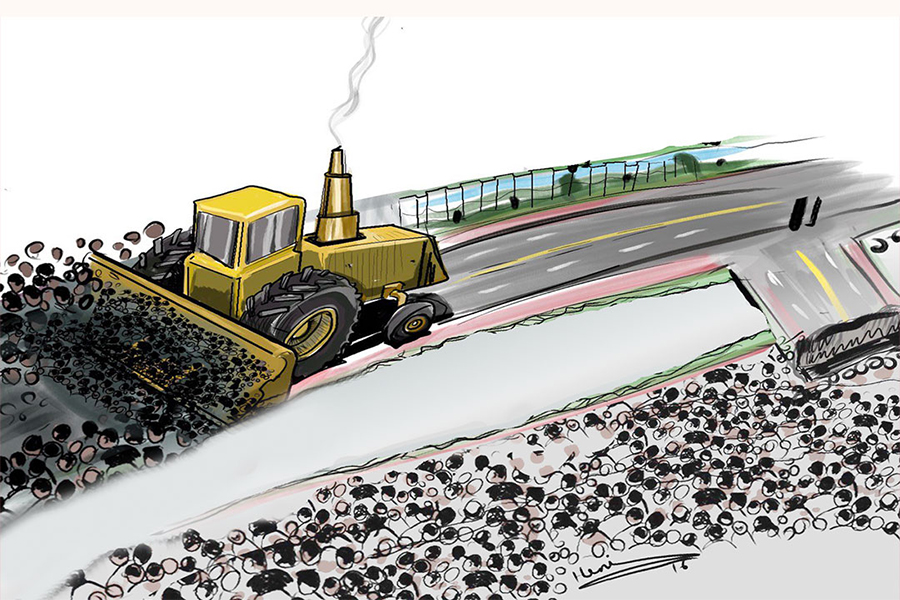

Construction authorities have unveiled a price adjustment implementation manual for s...

Sep 14 , 2024

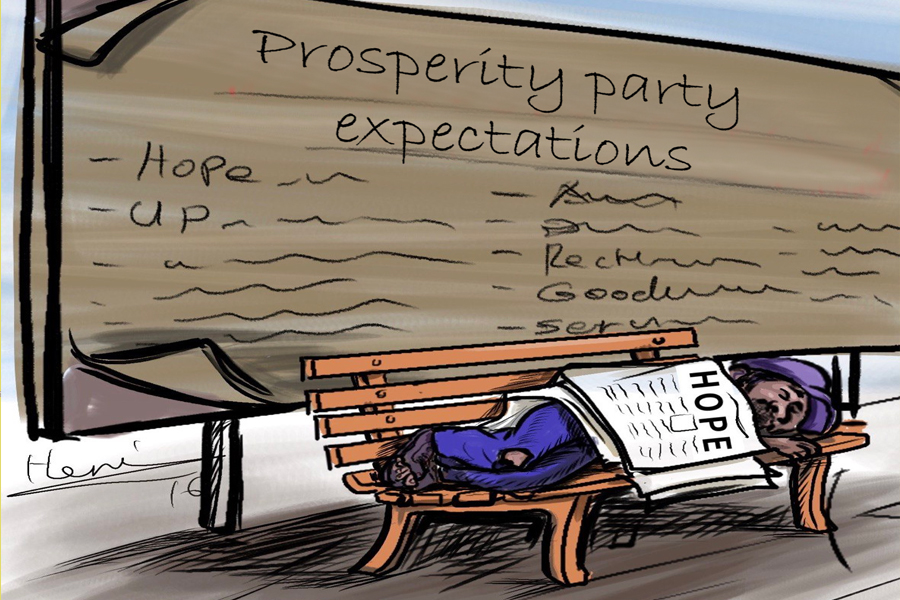

Successive regimes share a common legacy: a deep-seated commitment to education as a...

Sep 8 , 2024

Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed's (PhD) visit to China last week could mark a watershed mom...

Sep 1 , 2024

Addis Abeba's skyline is being dramatically altered. Once characterised by unremarkab...

Aug 25 , 2024

It may appear distasteful, unappealing and cumbersome to sight. But, the Addis Abeba...

Sep 14 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

The stalls of Atkilt Tera market in Addis Abeba were uncharacteristically empty. Onio...

Sep 14 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Federal authorities are proceeding with a wage reform for the public service, a long...

Sep 14 , 2024 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

A new directive regulating food additives has been introduced, marking a step in safe...

Sep 14 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

The Civil Registration & Residency Service Agency (CRRSA) has undergone a major o...